|

|

|

|

|

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

When Henry Beston left the Great Beach of Cape Cod in the autumn of 1927, he had discovered himself as a writer. It was here that he found his subject, his voice, his philosophy. Over the course of the following year he would distill these into his masterpiece, The Outermost House. The book was published in the fall of 1928. With its publication, Beston's reputation as a writer-naturalist began to grow. He married fellow writer Elizabeth Coatsworth in June 1929; they took up residence in Hingham, just south of Boston, and looked forward to a long life together, writing books and building a family. When Henry Beston left the Great Beach of Cape Cod in the autumn of 1927, he had discovered himself as a writer. It was here that he found his subject, his voice, his philosophy. Over the course of the following year he would distill these into his masterpiece, The Outermost House. The book was published in the fall of 1928. With its publication, Beston's reputation as a writer-naturalist began to grow. He married fellow writer Elizabeth Coatsworth in June 1929; they took up residence in Hingham, just south of Boston, and looked forward to a long life together, writing books and building a family.

But not in Hingham.

"Henry did not like this life with its grind of passing cars and its quality of an old South Shore village slowly turning into a suburb," Elizabeth later recalled. Henry and Elizabeth occasionally visited Cape Cod, staying at The Fo'castle (Henry's official name for his little house) or a boarding house in Eastham; but while Henry considered writing a book about the inland Cape, and composed a couple of chapters, he soon abandoned the effort; and he and Elizabeth never considered becoming full-time residents of the Cape.

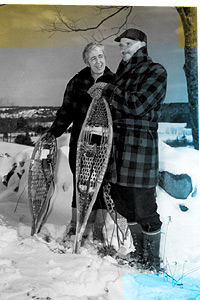

Henry had discovered the path of his working life on the Great Beach, but there was something else he had yet to find. He found it in 1931, houseboating on a Maine lake with a friend: Chimney Farm, a span of pasture land, hayfields, and wooded acres with a timbered barn and a faded yellow farmhouse overlooking Damariscotta Lake. Chimney Farm, so-called for the five brick chimneys that rose above the farmhouse roof, was for sale. Acting on impulse (with a quick assent from Elizabeth), Beston bought it. He had repairs made, installed indoor plumbing, and painted the house, as Elizabeth recalled, "a strong farmhouse red." In Chimney Farm he found the place, and the mode of living, that would define the rest of his life. He found his home.

As you probably know from reading The Outermost House, Henry Beston believed that the remedy for modern, Western humanity, living in a world increasingly artificial and estranged from nature, lay in a closer communion to the lasting facts of earthly existence: the seasonal progression of the sun, the migrations of animals, the cyclings of the stars, the smells of summer sand-dunes and September hay. At Chimney Farm, he determined to live a simpler life than that of his contemporaries. He chose, as he might have put it, a country life, filled with country truths. Northern Farm, published in 1948, is his testament to that life.

Like The Outermost House (as well as Walden, and much of our nature writing since then), Northern Farm adopts a "year-in-the-life" approach, the chapters carrying us along through the seasons of a single year. What he had written originally as a series of country-living columns for The Progressive magazine, Beston realized, was perfectly suited for publication as a book. Each short chapter moves us a little farther along in the yearly cycle; each is followed by a short, apparently unstudied snatch of notes from Beston's "Farm Diary" --- which will show you that he did not, invariably, spend a whole morning to polish a single sentence; and each is finished with a paragraph or two of Beston's philosophical musings on man, machinery, and nature.

With the exception of the diary entries, these compositional elements were all present in The Outermost House. But Northern Farm is a less fluid execution than the year on the beach: where description and philosophy were seamlessly merged in The Outermost House, they are cut-and-pasted, less flowing than forced, in Northern Farm. The narrative of Outermost House flows and ebbs like the tides, or the swash and retreat of waves on the beach; an incident seen today recalls one seen a month ago, and present observation and past recollection merge like smooth waters. We follow the events of one year, yes, but within that year are the echoes and suggestions of geological time. By contrast, Northern Farm remains largely in the present tense. The events of Beston's daily life skirt the shoals of self-indulgence, and the sense of long time, natural continuance, is no longer so foundational, so implicit in the writing.

Still, Northern Farm contains passages as beautiful and clear and flowing as a New England brook, and, as in Outermost House, there are quotable sentences on every page. Beston transports us to a vanished time when Maine farmers used horses, people traveled by train, and women darned socks by kerosene lamps as their husbands studied the seed catalogs and stoked the woodstove. This is the Maine of red-plaid shirts and Grange pancake suppers, of mowing with scythes or horse-drawn mowers, when winter meant the smell of wet wool by the kitchen stove and no one had thought of putting goose-down into a jacket. So far does all this seem from us today, that Beston's world might be that of Richard Jefferies, writing in late-19th century, rural England. Still, Northern Farm contains passages as beautiful and clear and flowing as a New England brook, and, as in Outermost House, there are quotable sentences on every page. Beston transports us to a vanished time when Maine farmers used horses, people traveled by train, and women darned socks by kerosene lamps as their husbands studied the seed catalogs and stoked the woodstove. This is the Maine of red-plaid shirts and Grange pancake suppers, of mowing with scythes or horse-drawn mowers, when winter meant the smell of wet wool by the kitchen stove and no one had thought of putting goose-down into a jacket. So far does all this seem from us today, that Beston's world might be that of Richard Jefferies, writing in late-19th century, rural England.

Into this portrait of a fast-receding, pastoral world, Beston paints the colors of the natural year; and here, as always, his eye and ear and language find their truest mark. He contrasts the shadows of winter with those of summer, finding the one astronomical, the other organic …. He listens attentively to the sighing of the pond ice on a February night, unsettling in its eerie, mystical music … He visits Damariscotta Mills to watch the alewife run, seeing in them the indomitable spirit of life, climbing and fighting, struggling on.

In these and other passages, we sense again the urgency of what Beston has told us: that these are the things that went before us, and must come after, the very ground of our humanity. He reminds us that we must not forget but honor this older world, if, despite the technology and haste that would tear us away, we are to be truly human.

Northern Farm is not, certainly, the equal of The Outermost House. But it is vintage Beston. The prose is unequalled, the images unforgettable, the message undeniable. If you read one book by Henry Beston, make it The Outermost House; if two, add Northern Farm. If three? You'll find our answer elsewhere in this website, but we will give you a hint: For a thoughtful and comprehensive portrait of Beston's life at Chimney Farm, read Roger Swain's introduction to the 1990 edition of Beston's first Maine book, Herbs and the Earth, first published in 1935, and now available from David Godine.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

|

|

|

|

|