|

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH KATE BESTON

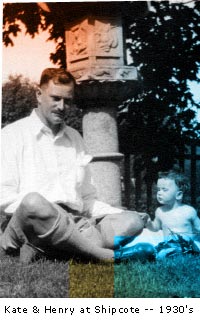

Kate Beston Barnes, born April 9, 1932, the second daughter of Henry Beston and Elizabeth Coatsworth, lives today in Appleton, Maine, a half-hour’s drive from Chimney Farm.

True to her lineage, Kate is a distinguished poet, and served, in the early 1990s, as the first Poet Laureate of the State of Maine. She has recently published her latest volume of her poetry, Kneeling Orion; and when we talked with her in May 2004, we were delighted to find that she answered some of our questions --- about Henry and Elizabeth and life at Chimney Farm --- with poems. A transcription of our interview with Kate follows.

What was it like for you and Meg as children, growing up on a rural Maine farm as the daughters of two famous writers? What was it like for you and Meg as children, growing up on a rural Maine farm as the daughters of two famous writers?

K: Well, we had no idea we were the daughters of famous writers. And they were not, I think, particularly famous writers at that point --- they were just full-time, hard-working writers. My parents were not media people, in the modern sense, in any way. When Meg and I were growing up, we spent the winters in Massachusetts, where our school life went on. I only went to school in Maine for one year. I did, however, have a very strong sense of the road --- East Neck Road in Nobleboro, where Chimney Farm is --- as our social unit, our immediate community; and my parents were not the kind of "from away" people who don’t make friends on their road --- they made themselves part of their community.

Now, I was just a child before World War II, and at that time the people of Nobleboro were still engaged in subsistence farming, living off their land. It was very beautiful, and everyone was closely tied to those natural cycles that my father celebrated in his writing. We didn’t get electricity until I was in college.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

We can picture a farmhouse full of books, lit by kerosene lamps . . .

K: Well, they were certainly readers. The house was full of books. As I’m sure you know, we all have to prune our books, or we’d be pushed out of house and home by them. My father’s books filled up the Herb Attic, where he worked; and then, he and my mother had so many books they had to move some to the woodshed; and then he had a room made up in the loft of the barn --- he called it The Barnatheum; and then another room was attached to that, and of course the books suffered terribly. I remember a constantly expanding volume of books, which they could never bring themselves to part with.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

What did Henry find at Chimney Farm that inspired him to make his adult life there? What did Henry find at Chimney Farm that inspired him to make his adult life there?

K: He had been looking for a place that was beautiful, and that had a certain amount of historical tradition, and that was, still, a landscape of subsistence farming. I suppose that’s how we’d put it now, but those are sort of sociological-sounding words, and his feelings were not sociological. He had been up there with Uncle Jake Day, camping out on The Ark, Uncle Jake’s houseboat, and he had fallen in love with that landscape and Damariscotta Lake. The farm came up for sale --- the people who’d bought it from the original owners had logged the place and then put it on the market --- and my father just immediately knew that he wanted it. My mother had never seen it, but when he told her about it she trusted him, and they bought it.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

In all of Henry’s writing, he sought and emphasized a close and traditional relationship between a people and their landscape, and he was one of the first to see how rapidly that relationship was eroding. How do you think he arrived at his sense of that land-based tradition and its importance to human life?

K: Well, the Quincy, Massachusetts of 1888 was not the roaring suburb that it is today, and he would have seen a lot of working farmland growing up. But you know, we live in a time when there always has to be a psychological explanation of things --- it’s just the mode of our era, I guess. In my father’s case, that feeling might be traced to his mother, who was French and whom he loved very much. She died when he was eight, and he always missed her. After he finished at Harvard, he went abroad and taught at an extension that Harvard had in Lyons, France; and during that year, he got an incredible, deeply felt sense of a traditional landscape --- a sense that informed the rest of his life. This was before the First World War, and I think that year in France was one of the things that moved him, in 1915, to become a volunteer in the ambulance corps, before America entered the war.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Can you tell us something about the writing habits of your father, versus those of your mother?

K: Let me read you a poem. It’s called "At Home," from a book called Where the Deer Were:

My mother, that feast of light, has always sat down,

Composed herself, and written poetry, hardly reworking any,

Just the way she used to tell us

The Chinese painters painted.

First they sat for days on the hillside, watching the rabbits;

Then they went home. They set out ink and paper, meditated,

And only then picked up their brushes

To catch the lift of a rabbit in mid-hop.

"If it didn’t come out, I would throw it away."

Oh, she is still a bird that fills the bush with singing ---

The way she touches her teacup; the look she gives you

As you sit across from her. It is all a kind of essential music.

I also remember my father, alone at the dining room table,

The ink bottle safe in a bowl, his orange-red fountain pen in his big hand.

The hand moved slowly back and forth, and the floor below was white

With sheets of paper, each carrying a rejected phrase or two

As he struggled all morning to finish just one sentence,

Like a smith, hammering thick and glowing iron ---

A Jacob, wrestling with the astonishing angel.

That pretty well tells it, I think. In some ways, you know, I think my father was a man of one book. He never said this, but I think he always wanted to write something that would reach the depths of The Outermost House, and although people have loved Northern Farm and Herbs and the Earth, I’m not sure that he really felt he had ever reached those depths again. I do remember that he felt a strong obligation to the reader. He had worked a while as a newspaper reporter, and he was fond of a remark he’d picked up, a sort of test: Will the reader turn the page? And I think that this is a very important question for a nature writer to ask him- or herself. There is often very little human story in nature-writing, and without that you can lose your readers very quickly. My father had a generous and humanly warm spirit, and I think his world was filtered through that spirit onto his page.

I remember, too, that the place in which he wrote was always important to him, as though if he could just be completely comfortable with where he was, the writing might come easier. When we lived in Hingham, Massachusetts, he would rent studies away from the house. At Chimney Farm, he wrote for a long time up in the herb attic. Then he had a study out in the woods, made from an old loggers’ block-house that they used to move from place to place by oxen. He had that house moved several times, and he was never satisfied, quite. Finally he had it moved by oxen down into the front field above the lake, where it’s been mouldering ever since.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Did Henry talk like he wrote?

K: He did. Yes, he did: he talked in sentences and paragraphs. He had a wonderful ear. When he was in college, he’d been in a production of "Hamlet". He’d fallen in love with it, and I think without much difficulty he’d learned all of it by heart --- everybody’s part, every word. He was very particular, very precise, about the meanings and pronunciations of words. I remember discussions and arguments around the dinner table, and he would always win when it came to words --- on the most unlikely things. I remember, for example, that one preferred pronunciation, at that time, was "oc-TO-pus," and that was the kind of thing he would know.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

How did your mother and father meet?

K: Oh --- listen, could you stand one more poem? This is called "Old Roses," and it’s in my latest book:

When my father met my mother

At a dinner party in a garden of very old roses

On Beacon Hill one hot evening in early June,

He said to his friend, F. Morton Smith, that night,

"Morton, I have met the girl I’m going to marry."

(We have Uncle Morton’s testimony for that, the certified word of a Boston lawyer.)

My mother

Said my father had looked handsome, yes,

And talked delightfully. But what she remembered were the mosquitoes.

If she stopped slapping at them, even for a second,

You were eaten up alive.

My father courted her for the next ten years

Whenever they found themselves in the same place.

It was the twenties then, heyday of ocean liners, and she might be

In Paris, or maybe off getting run away with

By a hairy, two-humped camel, in the Gobi Desert

While he was crossing the Pyrenees on foot.

But at last, on another steamy hot day in Massachusetts, as she,

Still wet from the bath, lay naked upstairs on her sister’s bed,

She heard the wedding march start up on the grand piano directly below her.

She sprang to her feet, threw on her cream-colored dress with the dipping hemline,

And flung herself down the narrow old staircase

Straight into the arms of matrimony,

Which were wearing an English jacket of dark blue wool for the occasion,

Splendid but unendurable.

Would anyone say the marriage was a happy one?

I don’t think I know. Sometimes, perhaps.

I can’t imagine either of them with anyone else.

Years later, I, a greedy child, crouched in the dark cabinet under the attic stairs

And wolfed down the last slice of their wedding cake,

Dried-out fruitcake in a little box covered with silver paper

And lined with paper lace, a keepsake for wedding guests

To slip under their pillows that night

So that they too would dream the bright moon

Rolling her way through silver light, singing stars clustering under the clouds.

Those crumbs became the bones in my seven-year-old body

And they’re in there yet, while the dreams

Sing on in my head forever,

Like mosquitoes, whining among the leaves of thorny old roses.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

In your poem "Coming Back," there’s a verse where:

"I hear my dead father

Still grieving and raging downstairs like the minotaur

in the palace cellar; like water

my mother’s voice goes on soothingly.

Sleep now."

To one familiar with Henry’s prose, so confident and serene, sure and magisterial, this reference to grief and rage is surprising.

K: Oh, well, think again! You see, all of us who write put our best selves into our writing, so that the reader’s impression of the whole person is bound to be skewed. They say, you know, that people are often keen to meet a favorite writer, then disappointed when they do --- and they shouldn’t be. People put their best selves into their writing, and they should --- but there’s a lot more to the living, whole person, and not all of it is happy.

Now my father was a tall, handsome man with an absolutely splendid presence; people were instinctively drawn to him, and they found him good-natured. And in his writing, always, he was absolutely sincere. Completely real. But his own father had been a man of notably bad temper, quick temper. And it was very hard for my father after his mother died. His brother, George, was a big football star, you know, and Henry was so different --- he wanted to read. And I think his father really made it hard for him to be who he was. Years later --- not in time to rescue my father, but at least in time to help --- his father married again, a New England schoolmarm who had a job of her own and wouldn’t put up with his temper. She straightened things up and defended my father, who always adored her. So anyway, I think, of necessity, Henry had some really dark places inside him.

Now my father was a tall, handsome man with an absolutely splendid presence; people were instinctively drawn to him, and they found him good-natured. And in his writing, always, he was absolutely sincere. Completely real. But his own father had been a man of notably bad temper, quick temper. And it was very hard for my father after his mother died. His brother, George, was a big football star, you know, and Henry was so different --- he wanted to read. And I think his father really made it hard for him to be who he was. Years later --- not in time to rescue my father, but at least in time to help --- his father married again, a New England schoolmarm who had a job of her own and wouldn’t put up with his temper. She straightened things up and defended my father, who always adored her. So anyway, I think, of necessity, Henry had some really dark places inside him.

It’s interesting, too, that my father performed unevenly in school. He did brilliantly in the things he enjoyed --- history, English --- and very poorly in the things he didn’t, like math. He never did pass Harvard’s math requirement, and I think they finally just let it slide.

A lot of people could sympathize with that. In his nature writing, certainly, Henry’s response to the world is less scientific than sensual, quite different from much of the nature writing being done today.

That’s very true. You know, I read eagerly the nature poetry that people are writing today, and sometimes I think it’s too biological. I don’t want just biology, I want nature that’s been translated into English, into poetry. That may be an unjustified criticism, but it’s the sense I get from a lot of what’s being written.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Nature writing, since Henry’s time, has burgeoned into a large literary genre ---- yet many of the writers seem to focus their energies on the intricacies of evolution or the peculiarities of a certain ecosystem, steering clear of the larger ethical questions that concerned Henry: how do we create a human life, a human relationship to the Earth, for example, in an age of rampant technological and commercial development? What would Henry make of this trend, this turning away from the deep philosophical generalizations so crucial to him?

K: I wonder. You know, he was a bird that was going to sing its own song --- his song. I don’t think that he could have changed much, although I do know that he was influenced by the writing of his time. He liked D.H. Lawrence very much, or had when he was young. Elizabeth Bowen was a big favorite, and he very much admired the writing of Isak Dinesen --- he liked that perfection of craft. But I think he would have been horrified, just horrified, by the world of today. A lot of that grieving and raging was about what was happening in the world.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you think his "Chrome Millennium" has come to pass?

K: Well, this is a ghastly time, isn’t it? So far, Maine has managed to stave off a lot of what’s happened to the rest of the American landscape, but I’m afraid it’s just a matter of time.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

If you had to recommend just two books by each of your parents, which would you recommend, and why?

K: Well, that’s easier to do with my father than with my mother. Of Henry’s books, certainly, The Outermost House and Northern Farm.

With my mother, who published more than a hundred books --- poetry, children’s books, novels, reminiscence, memoir --- I couldn’t pick just two. I do have some favorites, though: Door to the North is one; and I’d have to include The Cat Who Went to Heaven, a beautiful little children’s book that won the Newberry Award; Sword of the Wilderness, her account of one of those seventeenth-century Indian captivities --- a great, exciting book. That’s three, and I could add a lot more. You know, my mother never, never blew her own horn. But she did tell me once that in 1929 she had more poems published than any other serious American poet --- not more than Eddie Guest, but more than any other serious poet. She wrote so much, and so well; the quality was always there. With my mother, who published more than a hundred books --- poetry, children’s books, novels, reminiscence, memoir --- I couldn’t pick just two. I do have some favorites, though: Door to the North is one; and I’d have to include The Cat Who Went to Heaven, a beautiful little children’s book that won the Newberry Award; Sword of the Wilderness, her account of one of those seventeenth-century Indian captivities --- a great, exciting book. That’s three, and I could add a lot more. You know, my mother never, never blew her own horn. But she did tell me once that in 1929 she had more poems published than any other serious American poet --- not more than Eddie Guest, but more than any other serious poet. She wrote so much, and so well; the quality was always there.

I do think it’s difficult when a husband and wife are both writers. There’s bound to be a tension there between them, in terms of production. And although my mother never said this, I do believe she turned to children’s books partly as a way of reducing tension between herself and my father. He was such a slow, laborious writer, and she was so fluid. My father wrote his prose as though it were poetry, agonizing over a single word or phrase, needing quiet and seclusion; while my mother could sit down at her desk with the household in an uproar, give herself a little shake, and just dive right into whatever story she was writing.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Your parents were both prose-writers, and you became a widely published poet, and the Poet Laureate of Maine. Your mother, though, had begun her career with three books of poetry? Was it she who led you toward poetry

K: I suppose so, though I didn’t know it at the time. My mother was always reading to us --- she was a wonderful reader --- and she read us a lot of poetry. Nobody ever said to me, "Be a poet," but I guess I was just drawn to it.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Henry was always drawn northward, and loved adventuring along the St. Lawrence. What did he find there that moved him to write about it?

K: I really don’t know. "Dark and true and tender is the North," as Tennyson said. In Maine, my father had found a home that suited him, and I think that for him, Maine became the North. More so than Canada. I think that when he referred to the North, he was thinking of Maine.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

In an article you wrote for the Maine magazine Down East, you said you didn’t "think it would be a mistake to say that my mother was in love with this world, my father with this place in particular." Can you elaborate on that? In an article you wrote for the Maine magazine Down East, you said you didn’t "think it would be a mistake to say that my mother was in love with this world, my father with this place in particular." Can you elaborate on that?

K: My father was deeply attached to his own land, deeply. He drew strength from it; he was like a tree with his roots down in it. My mother had been a great traveler before they were married, and she could be comfortable, really, almost anyplace in the world. After her father died, her mother took her and her sister to the Far East. And while their mother stayed in a nice hotel, my mother and aunt would go upcountry on expeditions, into places where no European woman had ever been seen. They were great adventurers, up to anything that came their way.

I remember once, when my parents were old, they visited a friend who lived on an island in Casco Bay. She’d built her house at the edge of a cliff, and one of the bedrooms was cantilevered out over the bay. This was in the autumn, when gales were blowing. Well, my mother insisted on sleeping out there over the edge of the cliff, in a four-poster bed with narwhal tusks for the posts; my father kept thinking about being blown off the cliff, and chose to sleep on the sofa in the sitting room. My mother slept in the bed, and if she got blown off the cliff, too bad. If you look at her books, you can see that my mother’s imagination could take her all sorts of places; that’s what I mean when I say she was in love with the world.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

When your father proposed to her after his year on the Cape, did she really tell him, "No book, no wedding"?

K: You know, I have never believed that, and I don’t know where it got started. Certainly, she never told me that, and I think she would have. I do know that he had proposed to her many times, and that when she finally said yes, they were eating Baked Alaska after lunch in the Boston Ritz.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

What’s the status of the farm right now?

K: Well, we sold all the woodland to a wonderful gentleman named Alexander Buck, who, with the help of another great guy named Keith Ross, is going to put it all under a conservation easement, which will protect it, hopefully, forever. This is important because very close to here, a lot of miserable cottages are going up, something you just hate to see. I still own the farm, and I’m still paying the taxes. Through the efforts of Gary Lawless and Beth Leonard, who’ve lived there and looked after the place for many years, and a group of interested people of like mind, we’re hopeful that we can establish something that will preserve the farm and honor the memories and contributions of my parents.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Why is it important to you to save Chimney Farm?

K: Well, of course, we’d all like to save our childhood homes if we could, but that’s personal to me, and not the point. I would like the farm to be preserved as it was, not just as a memorial to my parents, and not just as an example of a historical Maine farm, but as a living, quiet place where people could come to write, things like that. A place where people could learn about my parents, a place where people could continue my father’s work in behalf of the natural world. Such a place would interpret my father’s legacy to the public, would help to keep his work alive for future generations. Unfortunately, something like this requires an endowment, and as yet no one has come forward with that kind of funding. But we’re hopeful. My father’s little house on the Cape was declared a National Literary Landmark, you know, and perhaps Chimney Farm might become one too. We’re working on it, and we need all the help we can get.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

|

|