|

OTHER INFO: About Elizabeth Coatsworth

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

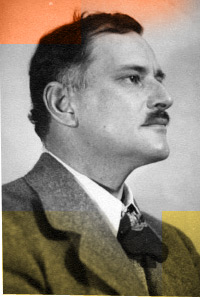

In September of 1926, Henry Beston Sheahan, 38 years old and single, went for a two-week vacation to a small frame cottage he'd had built on the sand-dunes two miles south of the Coast Guard station at Nauset, on Cape Cod. He had not intended to stay, but, as he recounted later in The Outermost House, "The fortnight ending, I lingered on, and as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go." Thus began a solitary sojourn on the beach, a thoughtful man's "year in outer nature;" the book that would bring that place, that year to life for legions of devoted readers; and the mature career of writer-naturalist Henry Beston. In September of 1926, Henry Beston Sheahan, 38 years old and single, went for a two-week vacation to a small frame cottage he'd had built on the sand-dunes two miles south of the Coast Guard station at Nauset, on Cape Cod. He had not intended to stay, but, as he recounted later in The Outermost House, "The fortnight ending, I lingered on, and as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go." Thus began a solitary sojourn on the beach, a thoughtful man's "year in outer nature;" the book that would bring that place, that year to life for legions of devoted readers; and the mature career of writer-naturalist Henry Beston.

Born in 1888 in the Boston suburb of Quincy, Mass., Beston was the son of an Irish-American physician and his Franco-American wife. He was educated at Harvard --- where, at his graduation in 1909, a prescient classmate inscribed his yearbook with a sketch of Henry's gravestone and the legend, "He Hated Machines" --- and he served with the volunteer ambulance corps in the First World War. By the time Henry first went to what he would later call "the Eastham sands," he was 36, and had been, by turns, an itinerant teacher in France; the author of a war memoir, a journalistic account of naval life, and several books of fairy tales and heroic stories for children; and the editor of The Living Age, an offshoot of the Atlantic Monthly which featured reprints of articles from British, French and German magazines for an American audience. Along the way, he had dropped his Irish surname and adopted his mother's maiden name, Beston, for his writing life.

At the little house on the Great Beach of Cape Cod, Henry Beston discovered his true calling as a writer. Here, alone with his thoughts and the vast panoramic sweep of life along the shore, Beston determined, in his journal, to become a "writer-naturalist":

"Nature," he wrote in French, "there is my country. The work--- to celebrate, to reveal the mystery, the beauty, and the rites of Nature, of the Visible World. To bind this feeling to my name."

Writing in longhand at the kitchen table overlooking the North Atlantic and the dunes, Beston produced a poetic, perceptive chronicle of nature's year, and our place within it. The rhythmic sweep and flux of the tides, the migrations of shorebirds, the shimmer of August heat and the fury of February storms, the march of constellations across the night sky: all were caught in the net of his senses and transmuted, indelibly, through the poetic power of his pen. Beston considered himself a poet of the landscape, bearing witness to the cycles and recurrences, great and small, of nature; and The Outermost House can be read as a single, sustained song, a lyrical meditation on the cycling pageant of the seasons. Writing in longhand at the kitchen table overlooking the North Atlantic and the dunes, Beston produced a poetic, perceptive chronicle of nature's year, and our place within it. The rhythmic sweep and flux of the tides, the migrations of shorebirds, the shimmer of August heat and the fury of February storms, the march of constellations across the night sky: all were caught in the net of his senses and transmuted, indelibly, through the poetic power of his pen. Beston considered himself a poet of the landscape, bearing witness to the cycles and recurrences, great and small, of nature; and The Outermost House can be read as a single, sustained song, a lyrical meditation on the cycling pageant of the seasons.

Prior to spending his year on the beach, Beston had fallen in love with Elizabeth Coatsworth, an accomplished poet and novelist. Leaving the Great Beach in 1927, Henry had a raft of journals, but not yet a book manuscript. When he proposed marriage to Elizabeth, she replied, "No book, no marriage." Henry spent the next year sculpting his musings and observations into The Outermost House; it was published in the fall of 1928, and the Bestons were married the following June. The book got good reviews, and began to develop a small but devoted list of admirers; its reputation persisted and grew through subsequent printings, until today it is universally recognized as a classic of American nature writing.

A few years after the publication of The Outermost House, Henry was visiting his friend, the painter Jake Day, on Day's houseboat, The Ark, on Damariscotta Lake in Maine. Already he had a strong affinity for Maine, but this time, learning of a farm for sale on a hillside rising from a cove of the lake, he acted.

"How would you like to have us buy a Maine farm?" he asked Elizabeth on his return to their home in Massachusetts.

"It sounds fine," she replied, and within a few weeks the Bestons were owners of Chimney Farm, in Nobleboro, Maine, where they would remain, writing and living and raising two daughters, until their deaths: Henry's in 1968, shortly after The Outermost House had been designated a national literary landmark; and Elizabeth's in 1986. Both are buried in a family cemetery on a low hill overlooking the farm and lake that they loved. (You'll find more on Chimney Farm, Henry's book Northern Farm, and Elizabeth's books elsewhere in this website.)

Henry Beston was a slow and painstaking writer, revising and polishing every sentence, every turn of phrase --- sometimes, as Elizabeth recalled after his death, taking an entire morning to complete one sentence. His literary output after The Outermost House was not great. Northern Farm, his book about life in Maine, was compiled in the late 1940's from a series of country-living columns he wrote for The Progressive magazine; he wrote The Saint Lawrence, a geographical and historical tour of the great seaway, for the "Rivers of America" series; he revised his children's books as Henry Beston's Fairy Tales; he edited an anthology on life in colonial America, and one on Maine; and he wrote Herbs and the Earth, a poetic meditation on herbs, history, the mysteries of the soil and the magic of growth. Of these, The Outermost House, Northern Farm, and Herbs and the Earth remain in print; the others can be found sometimes in Maine yard sales and used bookstores. An anthology of Beston's writing, The Best of Beston, is a reprint of an earlier volume, Especially Maine; it provides an excellent introduction to his work.

As our website grows, we hope to feature commentary on Henry Beston, Elizabeth Coatsworth, and Chimney Farm, not only from the writings of their contemporaries, but from prominent admirers who are writing today. In the meantime, we can recommend two insightful treatments of Henry's life and work:

Robert Finch's introduction to The Outermost House;

and Elizabeth Coatsworth's introduction to The Best of Beston.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Henry Beston Bibliography:

A Volunteer Poilu (1916)

Full Speed Ahead (1919)

Firelight Fairy Book (1919)

Starlight Wonder Book (1921)

Book of Gallant Vagabonds (1925)

The Sons of Kai (1926)

The Living Age (1921)

The Outermost House (1928)

Herbs and the Earth (1935)

American Memory (1937)

Five Bears and Miranda (1939)

The Tree that Ran away (1941)

Chimney Farm Bedtime Stories (1941)

The St. Lawrence (1942)

Northern Farm: A Chronicle of Maine (1949)

White Pine and Blue Water (1950)

Henry Beston's Fairy Tales (1952)

Especially Maine: The Natural World of Henry Beston (1972)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

ABOUT ELIZABETH COATSWORTH

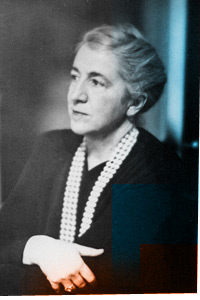

When Elizabeth Coatsworth married Henry Beston in 1929, she was thirty-six, he forty-one; and although in time his literary star would eclipse her own, on the day of their wedding --- and indeed, throughout her long life and prolific career --- Elizabeth stood in no man’s shadow. When Elizabeth Coatsworth married Henry Beston in 1929, she was thirty-six, he forty-one; and although in time his literary star would eclipse her own, on the day of their wedding --- and indeed, throughout her long life and prolific career --- Elizabeth stood in no man’s shadow.

Remembered today primarily as a graceful writer of children’s stories, Elizabeth Coatsworth, in her ninety-three years, published more than one hundred books in a wide variety of genres: poetry, novels, children’s books of travel and animals and adventure, personal essays and reminiscence. In 1929, the year of her marriage, Elizabeth saw more of her poems into print than any other serious American poet. She published her last book, the autobiographical Personal Geography, nearly fifty years later, at the age of eighty-four. In between, she said, she lived a life of "books, travels, children, household, and writing."

Born May 31, 1893, in Buffalo, Elizabeth was the second of two daughters born to Thomas William and Ida Reid Coatsworth. Her father, a prosperous grain merchant who’d inherited the family business, took the family traveling to broaden his daughters’ education and to avoid the harsh Buffalo winters. By the time she was six, Elizabeth had toured Egypt, the Near East, and Europe, and European travels continued throughout the winters of her girlhood and youth. At home, Elizabeth attended the Buffalo Seminary, a private school for girls where the classics were learned early and well, and Virgil was read in the Latin; she went on to Vassar, where she graduated as Salutatorian.

Still in her teens when her father died, Elizabeth continued to travel with her sister Margaret and their mother, journeying to China and Japan during the First World War. She was dark-eyed and tall, 5-foot-11, in love with the novelty of the world and game for adventure. While their mother stayed at a grand hotel in Peking or Shanghai, playing bridge or mah-jong with the other expatriate widows, Elizabeth and Margaret traveled into the hinterlands, hiring sampans, camels or horses, and sometimes venturing where no white woman had ever been seen. Elizabeth had grown up on the exotic tales and stories of Kipling’s India; now, seeing the Far East for herself, she was entranced by the land, the people, the poetry and painting. She published her first book of poems, Fox Footprints, a sort of homage to the Orient, in 1923.

Self-effacing and reserved, Elizabeth would later represent herself as having been an overly tall, awkward girl and young woman, ill at ease in social settings. In fact, she was wooed by suitors including William Beebe, the naturalist/writer/deep-sea explorer; and the future general George S. Patton. (As a young poet, Elizabeth once spent a weekend at the home of Amy Lowell, whose verse she admired. Lowell, who had an affinity for young women, came into the bathroom and sat nearby while Elizabeth lay in the bath --- where Elizabeth remained, decorous and shivering, until the water was cold and Lowell finally left the room.)

Margaret Coatsworth married F. Morton Smith, a Boston lawyer who had a Beacon Hill address and an old Harvard classmate who’d written a few moderately successful books and had recently dropped his Irish surname to become Henry Beston. As recounted by their surviving daughter, Kate Barnes, in a poem called "Old Roses," Elizabeth and Henry met in a summer rose garden at a Boston party, all white linen and perfume and mosquitoes; and Henry told Morton that night, "I have met the girl I’m going to marry!" He was right, of course, but his ten-year courtship of Elizabeth was no rush to the altar.

"It was the twenties then," as Kate tells it, "the heyday of ocean liners. She might be in Paris, or maybe off getting run away with by a hairy, two-humped camel in the Gobi Desert, while he was crossing the Pyrenees on foot" ---

but eventually, the summer following publication of The Outermost House, they were married. (Kate, incidentally, discounts the legend that Elizabeth withheld her consent with a "No book, no wedding" ultimatum. "She’d have told me that," says Kate. "It’s too good a story for her to have kept.")

At first, the newlyweds lived in a house in Hingham; but Henry grew restive there, and longed for unspoiled, pastoral country. As Elizabeth wrote in her introduction to Especially Maine: The Natural World of Henry Beston from Cape Cod to the St. Lawrence (republished in 2000 by David R. Godine as The Best of Beston), "Henry did not like this life with its grind of passing cars and its quality of an old South Shore village slowly turning into a suburb." And so, with one daughter now (Margaret, born June 30, 1930), and a second on the way, Henry returned to Hingham from a 1931 summer trip houseboating with longtime friend Jake Day on Damariscotta Pond in Maine to take Elizabeth out for a lunch of fish-sticks, and to ask her a question.

"How would you like to have us buy a Maine farm?" he asked; and Elizabeth replied immediately, "It sounds fine."

They bought Chimney Farm a few weeks later, and in the spring of 1932, while Elizabeth remained in Hingham, giving birth to their second daughter, Catherine (or Kate), Henry supervised renovations on the old farmhouse that would become the family’s home. They spent summers there during the 30’s and early 40’s, keeping the house in Hingham and the Fo’castle on the Cape, to which they seldom now returned; and by the end of the Second World War, Maine had become their permanent home.

During these years of "books, travels, children, household, and writing," Henry Beston struggled to speak for what he saw as the wounded Earth --- and to re-awaken in his fellow men that appreciation and reverence for the natural world which, he believed, had always before sustained and given context to human life. He struggled to produce language equal to the task he set himself, often spending an entire morning on a phrase or sentence, and often failing. He raged and grieved over the state of the world, and sought a perfection of language that might change hearts; given this standard, he found even letter-writing an excruciating task. Elizabeth, meanwhile, set herself the less presumptuous task of telling stories --- often stories for children --- and wrote with a free, fluid abandon.

"She would sit down at her desk," Kate recalls, "and compose herself for about thirty seconds, like a horse getting ready to jump. And then she would be off, writing as fast as her hand could go." By day’s end, Elizabeth’s pages would be ready for the printer; and she seldom looked back.

Elizabeth had traveled widely in the world, and she traveled widely in her imagination: she wrote about The Cat Who Went to Heaven, and was awarded the Newberry Medal; she wrote about the Indian captivities of the seventeenth-century Maine coast; she wrote stories of girlhood adventure in Egypt and Asia; fantasy stories about fathomless lakes lost in trackless evergreen forests; she wrote essays and recollections of her life in Maine and travels abroad. While Henry suffered and struggled to articulate a message that might change the world, Elizabeth embraced the world of her experience and imagination, and sent her books forth to do what they might. Henry was the seer, the anguished prophet ever at work on a single, perfect sermon; Elizabeth, so nearly forgotten today, was perhaps the more natural writer, the clear and easy storyteller.

Steadily productive on her own, Elizabeth was also Henry’s tireless supporter, and edited the fine anthology, The Best of Beston; but, perhaps out of deference to her husband, perhaps out of a desire to avoid discord, she wrote relatively few novels or adult books once they’d married.

"She left the adult books to my father," says Kate, "and though she never said this, I suspect they had some understanding in that regard." Relatively little was said at Chimney Farm about Elizabeth’s work and achievements; and it was only after Henry died that Elizabeth would presume to set her latest published book out on the parlor table for visitors to see.

"Whatever their understanding," Kate says, "it was tacit and deep, and affected all of us. Interrupting my father was absolutely out of the question. He needed quiet seclusion, and he got it, often by having a separate outbuilding to write in. But my mother’s work, as though it were somehow less important, could be interrupted by any of us; and it was, constantly."

Henry, as Kate has suggested in her poetry, had a dark and tortured side; Elizabeth evidently did not. "She was so intelligent, so very kind," says Kate, "and more fun to be with than anyone else in the world. She was always so very alive, so vital --- and you could never forget her eyes: dark, dark eyes, with the bright intensity of a falcon’s."

Henry died in 1968, and was buried beneath a glacial erratic --- chosen by Elizabeth from a stone wall on the farm --- with an inscription that Elizabeth selected from The Outermost House. Elizabeth continued to live at the farm and to write, turning in her seventies to reminiscence and autobiography. She published her final book, the memoir Personal Geography, in 1977, and died in 1986. She too is buried in the family plot overlooking the farm and lake, with no inscription as yet --- and a poet daughter facing a daunting task.

"She would want it clear and simple, like her writing," says Kate, "and it’s up to me to do it. But I loved her so much, and she was such a wonderful person in the world, I just can’t sum her up in a few words."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Elizabeth Coatsworth Bibliography (Partial):

Away Goes Sally (1934)

Five Bushel Farm (1939)

The Fair American (1940)

The White Horse (1942)

The Wonderful Day (1946)

The Incredible Tales (1951)

The Cat Who Went to Heaven, (1930, Newbury Award)

The Littlest House, (1940)

Trudy and the Tree House (1944)

The Dog from Nowhere (1958)

Bess and the Sphinx, (1948)

The Peddlers Cart, 1956)

Indian Mound Farm, (1943)

Marra's World (1975)

Personal Geography (1976)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

|

|